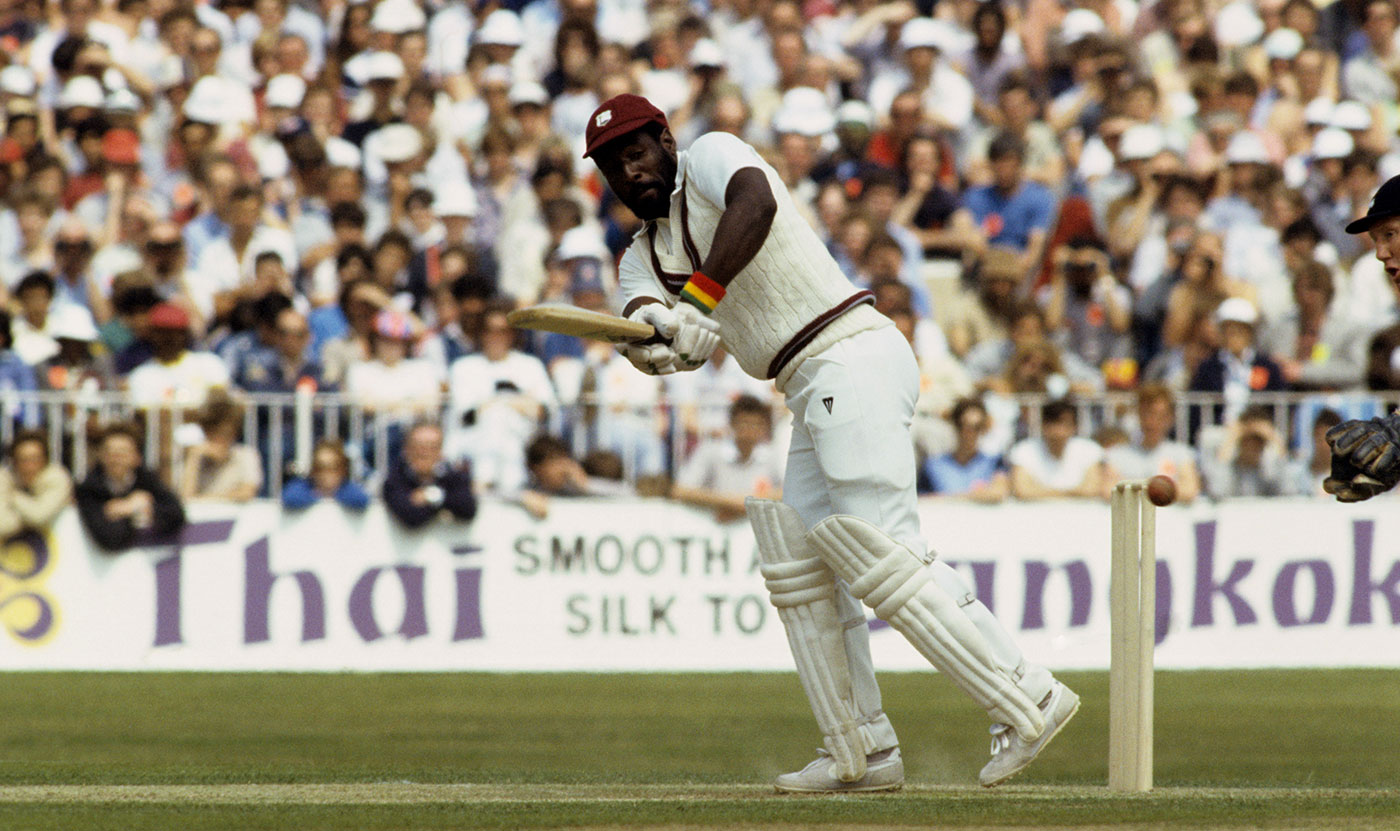

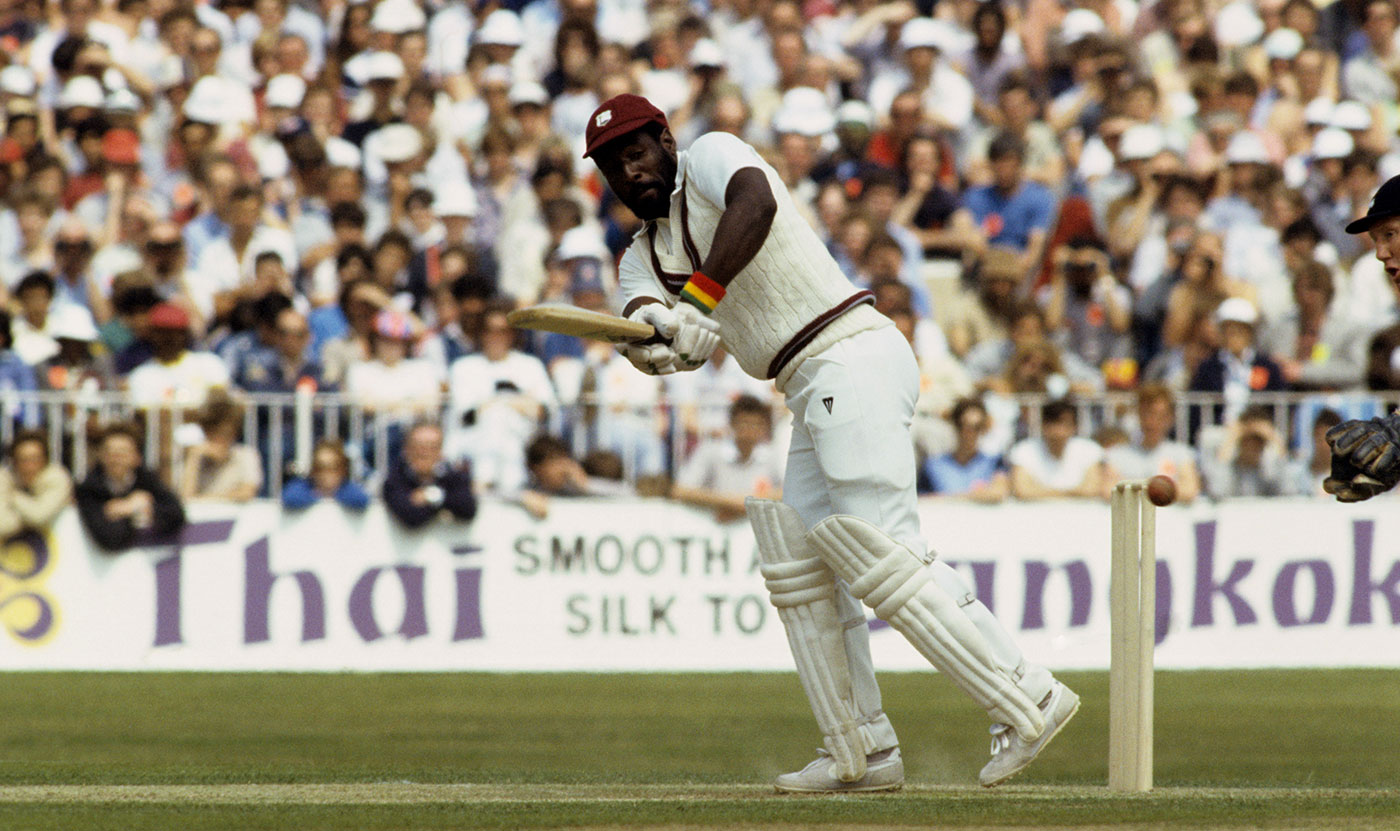

Flickin' awesome: Viv Richards clips a ball to leg on his way to 189 in an ODI at Old Trafford, 1984

Flickin' awesome: Viv Richards clips a ball to leg on his way to 189 in an ODI at Old Trafford, 1984

Four contenders. The IVA flick, the MSD stumping, the KP surge and... the great Sri Lankan dry-pitch con job

The Viv Richards leg-side flick

By Kamran Abbasi

You don't take Viv Richards down. I've seen him hit by a bumper and the ball slide off him like a sponge thrown at granite. I've seen him bowled for a duck and still swagger off the pitch. In the mind of King Viv these are simply moments of odd luck in a bowler's favour, for in his realm, in those royal 22 yards, an opponent is to be cut down with his SS Jumbo.

When you are growing up and you see a man like Richards bat, you want to bat like him. When you are older, you realise you'll never see a batsman like him again. We know about the swagger. Others swagger too, but it's never been so natural or intimidating. We know about the gum-chewing smile, bum jutting towards square leg in a straight-kneed stance, head cocked towards the bowler atop shoulders that seem as broad as the body is tall. We know what follows is beautiful brutality with no empathy for a bowler's impotence.

We hear much talk of modern batting, of switch hits and ramp shots. Richards didn't need any of those. Richards' style was to see ball, hit ball - anywhere. That isn't to say he couldn't play orthodox. His off-drive was quite upright but imperious; the ball might have been fired from a cannon. His pull was by arrangement with the bowler, who barely finished his action before Richards was swaying to the off side to thump him to the boundary. His on-drive was perfectly balanced, an exquisite blend of power and timing.

In defence, he'd pat the ball down as if it was the head of a docile kitten, to mock the lollipop deliveries of the world's most fearsome bowlers. But a Richards defensive stroke was a grand anticlimax, an obscene waste of talent. Here was a man made for destruction.

Speed, spin, late movement, early movement, the ball took a hell of a beating. When the mood took him, Richards stepped back a pace or two to free his arms and drive expansively through the off side. Whether it was a four or six was a matter of whimsy. It was unstoppable. It was signature. Indeed, all his moves were. He had so many signatures that you'd need an autograph book to capture them.

I've seen Richards hit by a bumper and the ball slide off him like a sponge thrown at granite. I've seen him bowled for a duck and still swagger off the pitch

I've seen Richards hit by a bumper and the ball slide off him like a sponge thrown at granite. I've seen him bowled for a duck and still swagger off the pitch

But the one that sticks with me is the way Richards played through leg. Yes, Richards was good off his legs. Fire one at his body and he flicked it away, as any world-class batsman might do, except with more venom. No, it isn't that routine stroke that interests me. Richards did something else, something more breathtaking, something that established his supremacy early in an encounter.

Batting at No. 3, he faced the world's best. Lillee and Thomson. Botham and Willis. Imran, Kapil and Hadlee. They spat venom and smelt blood. The pitches were rough, green or uneven. Richards didn't wear a helmet. They wanted to humble the mighty West Indies. They wanted Richards and his West Indians to grovel. Richards would smile. He'd swagger. He'd chew gum. He'd prod the pitch. He'd pat a few heads of docile kittens.

The bowler felt on top, so chest-thumpingly on top that he'd deliver a ball of perfect length darting in at off stump. Instead of patting back down the line, instead of stepping back and driving expansively through the off side, which it was too early to do, Richards had a third way. He moved with an effortless grace, as if merely readjusting that straight-kneed stance. His front leg moved forward and across his stumps, more across than forward, covering them, a certain lbw - for any man but King Viv, that is.

Next, Richards delivered his stroke, his signature move. Across his straight-kneed front leg, in a feat of immaculate timing and rippling power, he'd flick his hands over the ball, a flick that began as a twitch of his mighty shoulder pivots and ended with a snap of wrists, plucking it from its off-stump trajectory and pistoling it into or over the leg-side boundary. The message was delivered. King Viv was seizing control of his kingdom.

Forward and across, with power and poise, from straightened knees and mighty shoulders, he felled the world's best bowlers. They grovelled before him. If anybody else tried it, it looked like a slog, uncouth and uncultured. When Vivian Richards moved forward and across and flicked to leg, it was a shot of brutal beauty, a signature move to signal the demolition.

Kamran Abbasi is an editor, writer and broadcaster. @KamranAbbasi

****

The Dhoni stumping

By Sidharth Monga

Don't cross the line: unlike most keepers, when presented with a stumping opportunity, Dhoni doesn't step back to collect the ball, so he's quicker to knock off the bails

© Getty Images

The word "evolution" in the context of wicketkeeping frustratingly ends at how Adam Gilchrist turned that player into a batsman first and a gloveman second. Batting has evolved beyond recognition with the advent of the two limited-overs formats and the never-ending improvement in protective equipment and bats. Bowling has evolved with slower balls, reverse swing and the doosra. Wicketkeeping, a job behind the stumps, has only evolved in front of them.

MS Dhoni the wicketkeeper is different; yet when you think of a Dhoni signature it is always to do with his batting: the helicopter shot, the quick running, the calculated finish. I have not watched the Dhoni biopic, authorised and promoted by the man himself, and produced by his friend and manager, but none of the promos shows him keeping wicket, and I am willing to wager that the movie does not delve into that aspect. It is a shame because, with due respect to collecting throws in front of the stumps, wearing helmets while standing up to the quicks and the advance in general athleticism, Dhoni's stumping technique is the only evolutionary step in the actual art of wicketkeeping.

Wicketkeepers tend to follow the laws of physics when they collect hard cricket balls. Which is, take the hands back to absorb the blow and make sure the ball doesn't fall out. When it comes to stumpings, especially when the ball is turning and bouncing, keepers go back with the ball a little to collect it cleanly before moving towards the stumps. There is a precious half-second lost there. Dhoni doesn't go back. His gloves are always moving towards the stumps. It is as if along the way he just picks up a stationary object and whips the bails off with it.

It is an act whose finality is beyond doubt. You miss the ball with Dhoni behind the stumps and you know you have no time to get back. Usually on pitches with turn and bounce, you can always hope to return to the crease because the more the action on the ball the more a wicketkeeper has to go back with his gloves. This doesn't apply to Dhoni. The impact is most visible when batsmen are stumped playing the forward defensive. The ball dips a little and drags the back foot over, but it has to turn past the bat to beat it, which means a regular wicketkeeper takes that much time to allow batsmen to get back into the crease. With Dhoni you are stumped by the time alarm bells ring in your mind.

Dhoni almost never misses a stumping even though his hands are never going back to soften the blow. It is the reliability that makes it a signature move

Dhoni almost never misses a stumping even though his hands are never going back to soften the blow. It is the reliability that makes it a signature move

This is no party trick, and he has many - for instance, sticking his right leg out perpendicularly to stop a late cut, even as the hands follow the ball should it miss the bat. Dhoni almost never misses a stumping or a catch even though his hands are never going back to soften the blow. It is the reliability that makes it a signature move.

By all accounts, and by all I have seen in the India nets over the years, Dhoni hardly practises keeping. He rarely talks about it. His fielding coaches have little idea how he does it. Behind the scenes, though, he works hard and has done. He spends a lot of time on his wicketkeeping in his houses in Delhi and Ranchi. A current wicketkeeper on the circuit has had conversations with Dhoni about his technique and he says Dhoni can manage it because he has done it since he was a boy. Others don't even try.

At a young age, as with many things he did in his own way because of a mind that questioned norms, Dhoni knew he wanted to save time. I am not sure if he ever watched or spoke to the only man I have seen pull off such stumpings in international cricket, Sadanand Viswanath. Like Viswanath, Dhoni trained himself to not let his elbows go behind his body when collecting the ball standing up to the stumps. He never shied from wearing a helmet to protect himself; being effective was better than looking flash. Then hours went into perfecting the move. His strength, especially in the wrists, compensates for the control he loses by not giving himself time.

The result is an act of beauty that hasn't been given its due. Indian broadcasters nowadays seem to have a Kohli cam that captures everything Virat Kohli does on the field: running in with the ball, reacting to the delivery, to the shot, appealing, celebrating, despairing, cheering, fighting, scratching his beard. The Dhoni stumpings are already caught on tape from multiple angles, and before he goes for good, I hope some producer decides to play them out for the world on loop. That would be a trip.

Sidharth Monga is an assistant editor at ESPNcricinfo

****

The KP surge

By Rob Smyth

Yes, I can: Kevin Pietersen was at his best when battling the conditions, the situation, the opposition, and sometimes his own team

© Getty Images

I'll never forget Super Saturday of the London Olympics: Kevin Pietersen was batting. Pietersen's awesome 149 against South Africa at Headingley left a far greater imprint on my memory than the orgy of patriotism that accompanied arguably Britain's most celebrated day of sport. He didn't win a Test, never mind a gold medal, but the ethereal majesty with which he took apart the best pace attack in the world prompted a tremulous gratitude I shall always remember. The visceral thrill was such that it was impossible to sit still - and not just while the innings was going on. When I went home that night I tried to watch a film, couldn't concentrate and put the highlights of the cricket on, twice.

Pietersen was associated with many shots - the switch hit, the slog sweep, the flamingo - but his greatest skill was what we might call the KP surge: when he would decide, as if on a whim, to take a bowler or an attack apart; when his mere presence at the crease was a newsflash. It might only last half an hour or an hour. That was enough: the resounding impact of the Pietersen surge meant it was invariably match-winning. When he made a double-century against India at Lord's in 2011, his half-centuries came from 134 balls, 82, 85 - and finally 25 as he ran riot. He did not so much trouble the scorers as terrorise them. He did it against all opponents and in all contexts; he could kick an opponent when they were up or down. He did it in all formats too, but the elevated significance of his Test-match surges made them the most exhilarating thing I have seen in cricket.

The best things about watching sport are genius, unpredictability and partisanship. As an England fan, the Pietersen surge involved all three. It was an almost psychedelic experience. Those innings were a cure for shyness; they made you want to tell someone, anyone, that Pietersen was on one. In sport it's extremely rare for the reality to exceed the fantasy; with Pietersen that happened on multiple occasions. He didn't deal in the impossible; he dealt in the unimaginable, remixing existing shots and inventing new ones. It's no surprise that the majority of his most famous shots came during a surge, when he was in a higher state of concentration.

As a sports journalist you can become anaesthetised. The KP surge took me back to being a fan, and being a kid, lost in the wonder of astonishing sport

As a sports journalist you can become anaesthetised. The KP surge took me back to being a fan, and being a kid, lost in the wonder of astonishing sport

In his superb book Kevin Pietersen on Cricket, he observed that being in the zone did not, as we tend to think, mean seeing the ball big; it meant seeing it slow. Two shots demonstrated that better than others: the dreamy pull off Dale Steyn during his 149 at Headingley, and the laziest driven six over extra cover off Pragyan Ojha in his immense 186 in Mumbai later that year. There were a few exceptions, most notably the chest-beating duel with Brett Lee during his Ashes-winning 158 in 2005, but the Pietersen surge was usually defined by a serene control and an aura of invincibility. He gave the world's great bowlers a crash course in futility.

There was no pattern to when all this might occur, and he has struggled to understand the frequency with which he entered the zone. The most common trigger seemed to be defiance - of opponents, the media, poor form, or even, at Headingley in 2012, his own team-mates. He might be stimulated by the desire to show off, the match situation or the weather. In Colombo in 2012, he decided he simply could not bat time in the 45-degree heat. So he hit one six, and then he hit another, and soon he'd made 151 from 165 balls.

That aura of invincibility could be deceptive. For every legendary surge, there were three or four where he got himself out just as word was spreading that something magical might be happening. That jeopardy added to the thrill of the experience, and the reward when he pulled it off was that you could sit at close of play trying to fathom what you had just witnessed. As a sports journalist you can become anaesthetised. The KP surge took me back to being a fan, and being a kid, lost in the wonder of astonishing sport.

Rob Smyth is the author of Gentlemen and Sledgers: A History of the Ashes in 100 Quotations

****

The dry-pitch con job

By Andrew Fidel Fernando

Beware the Sri Lankan pitch, it has a switchblade in its back pocket

© AFP

If a government job is the most stable employment in South Asia, cricket administration is perhaps the most volatile. Cricket Australia has been stuck with James Sutherland for the better part of two decades. Giles Clarke looks and sounds like Jurassic calcium deposit, and upholds the hairstyle and values of an even earlier age. In South Asia - and Sri Lanka, in particular - cricket governance is forever enlivened by summary firings, interim-committee appointments, judicial injunctions, hostile takeovers, ad-hoc cocktail lunches, impromptu travel junkets, temperamental office Wi-Fi, and so on.

So when out of this chaos order emerges, it does seem wondrous. And in no instance do administrators, ground staff, team management and cricketers collude to such consistently fruitful effect as in the preparation of dry tracks for foreign teams.

It begins with the curator. In years gone by there may have been some head-scratching as to whether dry tracks are appropriate for certain visiting teams. Helpfully, the cricket world has since organised itself into two distinct groups: teams who can barely play spin, and teams who would rather self-immolate.

When the latter sort arrive at the ground, the curator smilingly assures them that, of course, there will be some pace and bounce, not to worry, it always looks like this before a Test, and actually, this is quite like the one that South Africa had won a game on a few years back, you'll see, and oh, put the opposition in to bat definitely. Not long after, he instructs his ground staff to scrub the surface down with coir brushes and warns them not to spill so much as a bead of sweat while they do. The curator has, of course, been instructed to prepare a surface just good enough to avoid ICC censure. Just to make sure, board officials are buttering up the match referee, their guest of honour in the extravagant pre-series tamasha.

Helpfully, the cricket world has since organised itself into two distinct groups: teams who can barely play spin, and teams who would rather self-immolate

Helpfully, the cricket world has since organised itself into two distinct groups: teams who can barely play spin, and teams who would rather self-immolate

By the eve of the match a little tension has built up, but the tourists are concealing their fears. The visiting captain will make assertive, leader-like comments at his media appearance. They know it will spin, but his men are up to the challenge, he will say. They have trained so hard, they are the best-prepared outfit not just in the history of cricket but also of preparation. And, he says, the top order did continuous trust-falls and sang around the campfire in their team-building jamboree until all memory of traumatic past tours was wiped out.

But then the match begins and things begin to go badly. The arm ball proves destructive initially, so the batsmen meet and decide to watch closely for it. The turning ball duly wreaks havoc the next day. Soon they begin to speak of spin bowling as if it is some kind of voodoo. Physically they are deteriorating, like someone is sticking pins into dolls made in their visage. Batsmen are sweating profusely in the heat. They are developing tinnitus from the constant cawing of the vultures around the bat. The legs are not quite moving as they should. The bowler's variations look identical out of the hand, so maybe the eyes are packing up.

By now, almost everything the home spinners touch is turning into a wicket. They had smiled graciously while the fast bowlers were given their token two overs with the new ball, but before long, lost patience and strode to the bowling crease to dispatch them to the boundary. "That was cute, machan, but it's time to really start playing now." For much of the game, the fast bowlers trudge from position to distant position in the field. By the end they have had less impact on proceedings than, say, the sightscreen attendants.

The home side eventually saunters to victory. The usual post-match reflection follows. About 48 hours pass. When another dry pitch is unveiled at the next venue, the visiting captain cannot drum up any bravado. This time he knows what he is really looking at: a funeral pyre.

Andrew Fidel Fernando is ESPNcricinfo's Sri Lanka correspondent. @andrewffernando

© ESPN Sports Media Ltd.