Facing up to the legendary Pakistani allrounder in his prime took not a little courage

July 5th 1980, Hove. Damp weather had taken a turn for the better and play began on time in the Championship match between Sussex and Hampshire. Keith Stevenson, an honest outswing bowler who had joined Hampshire from Derbyshire a couple of seasons earlier, quickly removed Gehan Mendis and Tim Booth-Jones. The pitch was true and quite pacy; Hove was a fine place for county cricket. The folk in their deckchairs and straw hats muttered disapproval at the loss of two early wickets but rather perked up when Imran Khan made his way to the wicket at No. 4, a place higher than on the card. Floating behind the Pakistan allrounder were great clouds of charisma.

He wore the Sussex cap and from its band flowed the signature mane that rested upon the nape of his neck. The martlets on his sleeveless jumper appeared as if newly embroidered and occasionally, when the morning sun broke, shone like little blue sapphires on his chest. Imran Khan was some sight. Outrageously handsome, athletically built and light on his feet, he carried himself like an emperor.

When he reached 15 or so, he closed the face of the bat too early on a little push to mid-on and the ball looped from the outside edge of his bat into the hands of the Hampshire left-arm spinner John Southern. It was a catch you would lob to a child. Southern dropped it. We shall never know why, though clearly he took his eye of it. I was stationed at midwicket and watched in horror, as did our team from their various viewpoints around the field. Hampshire weren't much good that year and such pickings were rare. The deckchairs talked in whispered words of disbelief and relief. Southern pulled his jumper from the back of his neck over his head in order to cover his face. The moment was frozen in time: Southern the subject of shame, Hampshire's team the subject of ridicule, Imran the benefactor of hopelessness.

"As flies to wanton boys are we to the gods; they kill us for their sport," says Gloucester in King Lear as he wanders on the heath after being blinded by Cornwall and Regan. The quotation reflects the profound despair that grips him and drives him to desire his own death. He suggests that there is no good order in the universe. Instead of divine justice, there is only the "sport" of vicious, inscrutable gods, who reward cruelty and delight in suffering.

We were Imran's sport that day all right. He made 114 high-class runs, hitting a six and 16 fours before racing up the hill in the final 40 minutes of the day to claim two wickets with fast inswingers that terrified the recipients, of whom I was one.

Early days: in the Lord's nets during the 1971 Pakistan tour of England

© Getty Images

Let's deal with the hundred first. Imran's batting was methodical, a thing of planning and practice. He had little of a Pakistani's wristy flair, and none of the looseness that has sometimes characterised the Pakistan game. He was a dodgy runner between the wickets, probably because he called runs from his own vantage point and not with another person in mind; but he didn't run much, at least not in the way of a run-thief. That was about the only flaw. We missed one of those too, Imran stuck halfway down with Paul Phillipson and the throw ending up across the boundary beneath the scoreboard.

He did everything else with time to spare and most of it with elegance. He played very straight - like gun barrel - and moved himself efficiently into line before looking almost exclusively to hit the ball back from whence it came. I remember the six he hit because it was exactly how he hit sixes: a little shuffle of the feet towards the bowler - Southern again - and then a lovely free swing of the bat that sent the ball sailing into the deckchairs. They more than whispered at that - they chortled and poured a glass of pale ale. He was out caught on the boundary off our other spinner, Nigel Cowley. I guess he was bored. Imran's return to the pavilion was the journey of a Roman triumph.

Soon enough he was back out, stretching limbs and wheeling arms. He took the new ball with Garth Le Roux, hardly a slouch himself. The change bowlers were Geoff Arnold and Ian Greig. We were lambs to the slaughter. Imran almost always bowled up the Hove hill and Le Roux down it, which was the case on July 5th 1980.

I repeat, he was a sight - sprinting in, leaping into his delivery stride and unleashing hell. The sprint was short-stepped and reached a good pace before the jump that, in his pomp, set him side-on and close to the stumps at the point of delivery. His left arm worked hard both as a part of the jump and in the follow-through, which, unusually for a fast bowler, broke away to the left and off the pitch area almost immediately after releasing the ball.

From the years at Oxford University in the early 1970s, when he was a chest-on medium-pace inswing bowler, he developed into one of the most sensational and adaptable fast bowlers of all time. Imagine if he had played the large part of his career in England, say, or New Zealand, rather than on the burnt-out, grassless pitches of Pakistan. Imagine the wickets column then! A loose wrist perfectly positioned behind the ball allowed for inswingers that were his stock-in-trade; the outswingers that he developed with the changes to his action were the luxury goods.

Swooning is permitted: in a Sydney gym in 1984

© Fairfax Media/Getty Images

Now here he was at Hove, the Pathan warrior, waiting for me.

First he bounced out Tim Tremlett, a fine county bowler made makeshift opener for a while. Then he pawed at the ground as I took guard - the kid with the crazy dream versus Imran Khan, the greatest cricketer Pakistan has ever known. He whistled a couple past my nose at such pace and with such steep bounce that I barely offered to play beyond a trigger move back and across the crease and the pick-up of the bat. These balls hammered into the wicketkeeper's gloves at head height 25 yards behind me. Then, half-ducking, half-fending, I gloved one that ripped back at me and shot past leg gully down to long leg for a single. The blow sent a surge of electricity through my nervous system, but I was off the mark and away from "Immy".

The umpire at Imran's end was Barrie Meyer. "We haven't met, son, but if I had anything to offer, I'd say stay down this end. You've got a chance against big Garth because you can see the ball in the hand all the way through the run-up and delivery. With Immy, it's lost and then suddenly appears like a bullet from a gun. Good luck." Oh, right. Thanks.

Hove was the quickest pitch in England. As so often in sport, the legend outlives the facts, but the difference on this day and on this surface between our popgun and their heavy artillery was, well, ridiculous. Even I bowled four overs for goodness' sake, and they had Immy, Garth, Horse and Greigy.

There is a tale about me not wearing a helmet but that was a year later, in a Benson and Hedges Cup match. It was a gorgeous day, the pitch was flat - flat like batting heaven - and yes, I wore a sun hat, the Majid Khan-style hat with a wide brim and a hint of style. As I walked out at No. 3 I heard Imran at long leg shout to Garth, who was bowling, "Look Garth, no helmet." They bombed me until the shell shock dismantled me. In defence, helmets were not de rigeur; in fact, they were a choice you made each day, for each pitch or opponent.

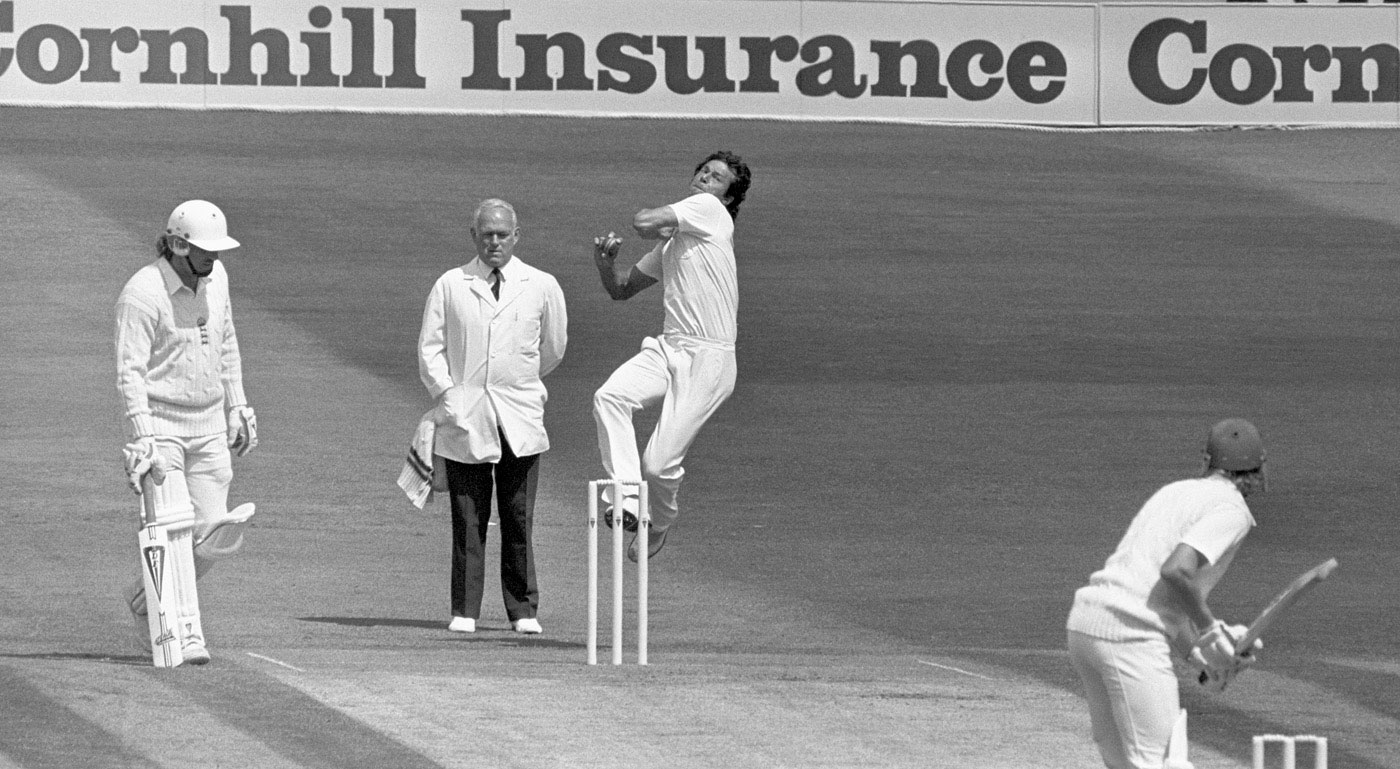

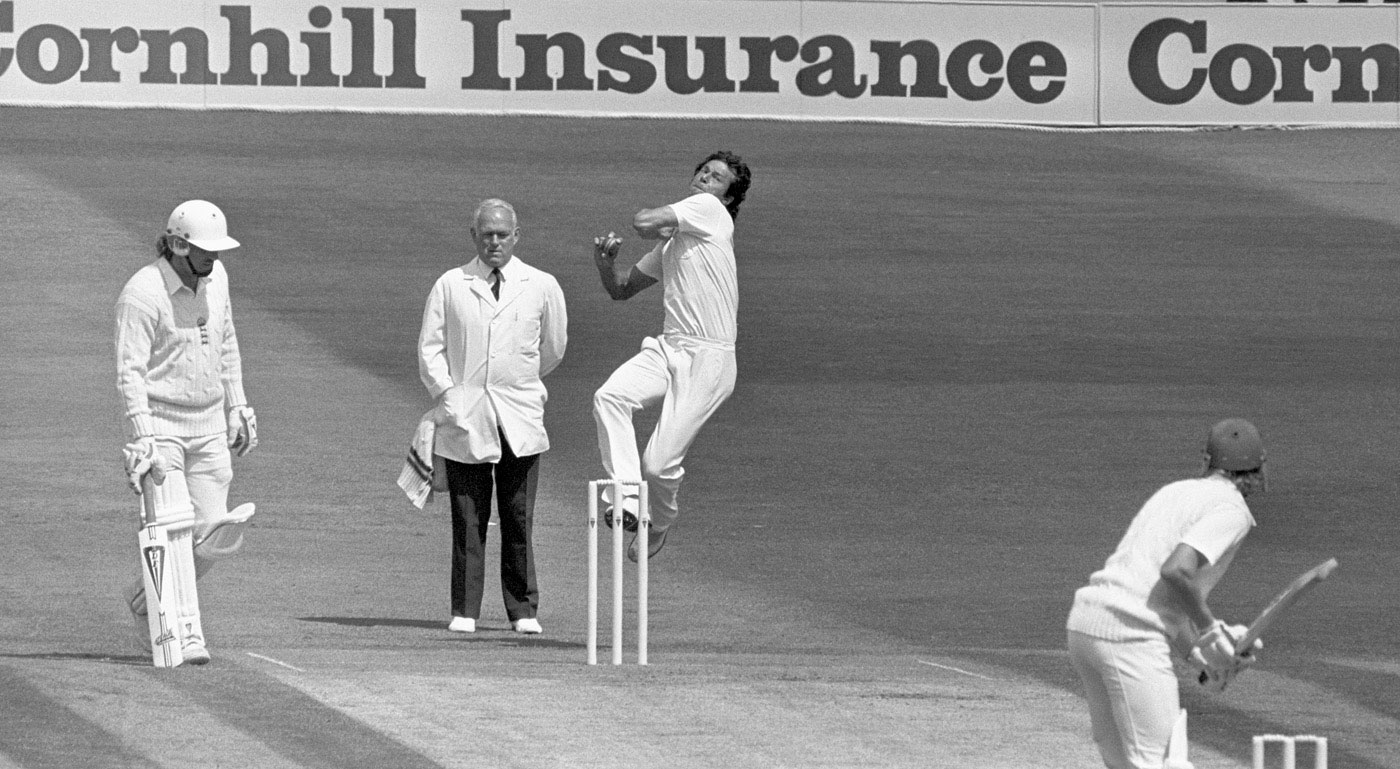

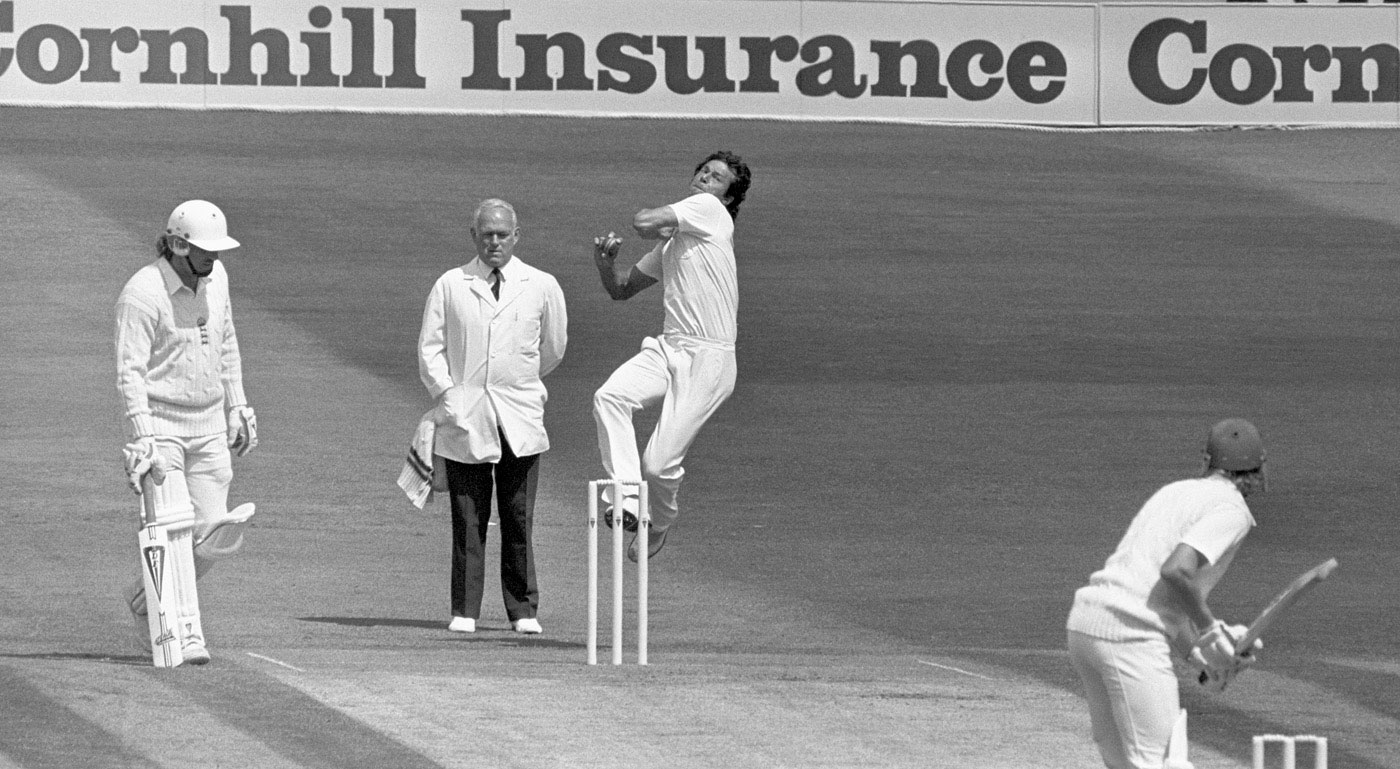

Flay as it lays: in action for Sussex in 1981

© Getty Images

On this day in 1980, I wore a helmet but had not worn one before and it was both cumbersome and tricky for sighting the ball - rather an important part of batting. The Perspex visor misted up - well, began to, but I wasn't there long enough for a blinding mist - and it extended a long way out from the face, so it was hard to tuck my chin into my left shoulder in my stance. Thus, I stood quite open, which would have been fine if I had practised that way, but in county cricket there was no time for practice, only play. Oh, and we had only a few helmets so they were shared around. I think mine was white, or blue, or green. I mean, please.

Anyway, Chris Smith sneaked a single off the second ball of Imran's next over and there I was, up the wrong end again. Looking back, it was a thrilling experience but at the time it quickly turned to humiliation. The gulf in standard was so big as to be dangerous. He got me out, of course he did. I nicked a bouncy thing around off stump and nearly shouted "Catch it!" to the keeper behind me. He dived to his right and did just that. I was immediately overcome with sadness at such inability. I was also embarrassed. Sitting in the dressing room, I welled up, reflecting on the truth that I wasn't good enough. It rained for most of the rest of the match, so there was no repeat or redemption.

Eight months later I had a phone call at home from Keith Fletcher. Didn't know him from a bar of soap but was mighty intrigued that he was on the end of the line. He asked me to come with an "England" side to play three matches against a combined India-Pakistan team in Dubai and Bahrain.

I roomed with Basil D'Oliveira, stood at cover for John Snow, and batted with Fletch and Graham Roope among others. Imran bowled a little below Hove pace in a football stadium on a matting pitch under floodlights. I was Man-of-the-Match and Immy, as I suddenly knew him, was friendly and complimentary at the reception that evening. I have been a fan ever since.

I first saw him live in 1979 at the Sydney Cricket Ground during World Series Cricket. By then he was really quick, and with Le Roux, Mike Procter and Clive Rice formed an attack good enough to beat Ian Chappell's Australians in the Supertest final. The cricketers all seemed so glamorous and we came to "see the white ball fly", as went the advertising slogans. Barry Richards made the hundred that saw the Rest of the World XI over the line and a new order of cricketing heroes emerged through the prism of rebellion.

Kerry Packer's astonishing raid on the game had seen most of the world's best players desert the established corridors and sign on to play in the closest thing cricket has ever seen to a rock 'n roll circus. It was a seminal moment, as big in sporting terms as the Beatles and as much fun as the record that changed the look and feel of the seventies, David Bowie's Ziggy Stardust. We watched open-mouthed as the Chappells, Rod Marsh and Dennis Lillee; Viv Richards, Clive Lloyd and Michael Holding; Barry Richards, Procter, Rice, Le Roux, Imran, Asif Iqbal, Derek Underwood and Tony Greig played with a white ball under lights, dressed in tight, coloured clothes with bell- bottom trousers and butterfly collars. These guys were Kerry's band, and boy, could they play guitar. Of them all, Viv and Immy shone brightest and played loudest. There was something of Hollywood in them both and the same aura remains to this day.

Imran (standing second from right) with the likes of Glenn Turner and Basil D'Oliveira in a Worcestershire line-up in 1973

© Bob Thomas/Getty Images

My next encounter with Imran was at the old Northlands Road Ground in Southampton in 1987. Hampshire were playing Pakistan in a warm-up game before the last Test and Imran came for a bat but not much else. In fact, he sent Mudassar Nazar, I think, to toss the coin, having hung around at the team hotel himself until the order of the game was decided and then cruised in at No. 7 for a hit late in the afternoon. He made 40-odd and didn't appear again until the third morning, when I suggested a declaration that would set up a lively day for the good crowd. We stood outside the club office, in front of an audience of spectators having an increasingly heated debate. He wanted practice for his team prior to securing what became a fabulous series win over England; I wanted a bit of enterprise and a run chase. I said he had a duty to the game, he said he had a duty to his team. He called me an arrogant public schoolboy, I said it took arrogance to know arrogance, and to and fro we went, like spoilt kids. The game fizzled out but within a few days Pakistan made 708 batting first at The Oval - Immy made 118 of them, Javed Miandad 260 - to end any hope England had of levelling the series, and, I guess, fully justifying the game plan at Southampton!

You could argue he was just a bit too cool for school during that match but Imran has always seen the bigger picture. He was an exceptional leader of men on the cricket field and has gone on to achieve the ambition most thought impossible, the leadership of Pakistan off the field. Of the myriad gifts, his greatest may be the way he holds it together under pressure. This is achieved through both resilience and self-belief; single-mindedness and desire. No one in cricket worked harder at being good. Imran's discipline and unwavering commitment were a locked-in motivation to those around him.

Of course, the 1992 World Cup was a crowning glory - a day for the ages - and provided the platform for another remarkable achievement. "In the speech, after we won the Cup, my mind was entirely focused on the hospital and I forgot to thank the team members who had put so much effort in the game," he has said since. Imran opened the Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital and Research Centre in Lahore in 1994. His mother, who was a cancer patient, had inspired it, and his speech that day at the Melbourne Cricket Ground will live with us always. He set up a second cancer hospital in Peshawar in 2015.

His route to becoming prime minister has at times been tortuous, needing both courage and persistence in the arguments for what he fundamentally believes is right. He is seen as populist: he pursues Islamic values, to which he rededicated himself in the early 1990s, and liberal economics in the creation of a welfare state. He favours clear and stringent anti-corruption laws and an anti-militant vision for a democratic Pakistan. In short, he is on another mission.

By the age of 30, Imran Khan was a cricketing god. At the age of 67, his real work appears only to have just begun. For those of us besotted by his deeds with bat and ball, we can for now reflect on a fantastic cricketer whose 362 Test wickets at 22.81 each and 3807 runs at 37.69 per innings put him alongside the greatest match-winners to have played the game. When choosing his favourite all-time team, Richie Benaud picked Imran at No. 7. For the record, here is that team - Hobbs, Gavaskar, Bradman, Tendulkar, Viv Richards, Sobers, Gilchrist, Imran Khan, Warne, Lillee, SF Barnes.

Enough said.

Mark Nicholas, the former Hampshire captain, is a TV and radio presenter and commentator

© ESPN Sports Media Ltd.