The former England batter was a beautiful man and a brilliant cricketer who took on the best and most threatening in the world and often won

There will, I think, be a party up in the sky. The talk will be of square drives and square cuts; of outswingers and inswingers. The laughter will come from days in combat and from nights in harness. The memories of five friends who trod different boards in the same cause and who then lit up the stages upon which they performed with distinction. The personalities were different but the spirit and character within them was shared. It will be one hell of a bash and the dust will only settle come the morning light.

Malcolm Marshall, Martin Crowe, Shane Warne and Mike Procter were already through the door; now Robin Smith joins them.

Crowe will urge Smith to play with softer hands. Procter will tell him to smash the spinners into the distant beyond. Warne will say, "I told you, Judge, it's simple, you're better than him, go take him down." Marshall will say, "Judgie, china, we gonna do this thing together." With Marshall it was always the two of them, together.

The depth in that relationship dated back to one time at a bar in Leicester where two hustlers were giving Macko a bit of racist lip. After a while, the bit became a lot, so Hampshire's two finest cricketers left to find something to eat. The hustlers followed them and moved up a gear, at which point Robin said, enough now. But they were not for hearing, so he said he'd hit the lead offender if he didn't shut the f*** up. But the fellow was still not for hearing, so the Judge gave him a very decent right hook. After which, the hustlers ran for their lives.

I relate this story because it is so uncharacteristic of the very special and gentle man who died 48 hours ago. Never can Robin be "judged" as a person by that moment, only as a friend. Neither, by the way, could his dangerously powerful square cut be used as evidence against him in that case, but only as evidence of his threat to a bowler. He was mortified by the whole thing, shocked that he had lost his cool, and sorry for such a reaction. Macko said it was the only reaction going and that Robin beat him to it by a second or two.

"Was it sudden?" my brother asked last night of his passing. Sudden, yes. Surprising, no. We (the cricket brotherhood he so missed) had all seen him during the Perth Test, which included an emotionally wrought Q&A session by him on the subject of mental health on the second, and last, day of the match, which led to a standing ovation at a corporate lunch. The next morning we had a Hampshire breakfast - Barry Richards, Paul Terry, Robin's brother Chris, and me. Robin was anxious that he had revealed so much of himself at the corporate lunch, but he still found time to remind us of stories past and matches never to be forgotten. He was very funny, a side of him not always seen, for shyness generally prevailed. On this bright Perth morning he had us in stitches.

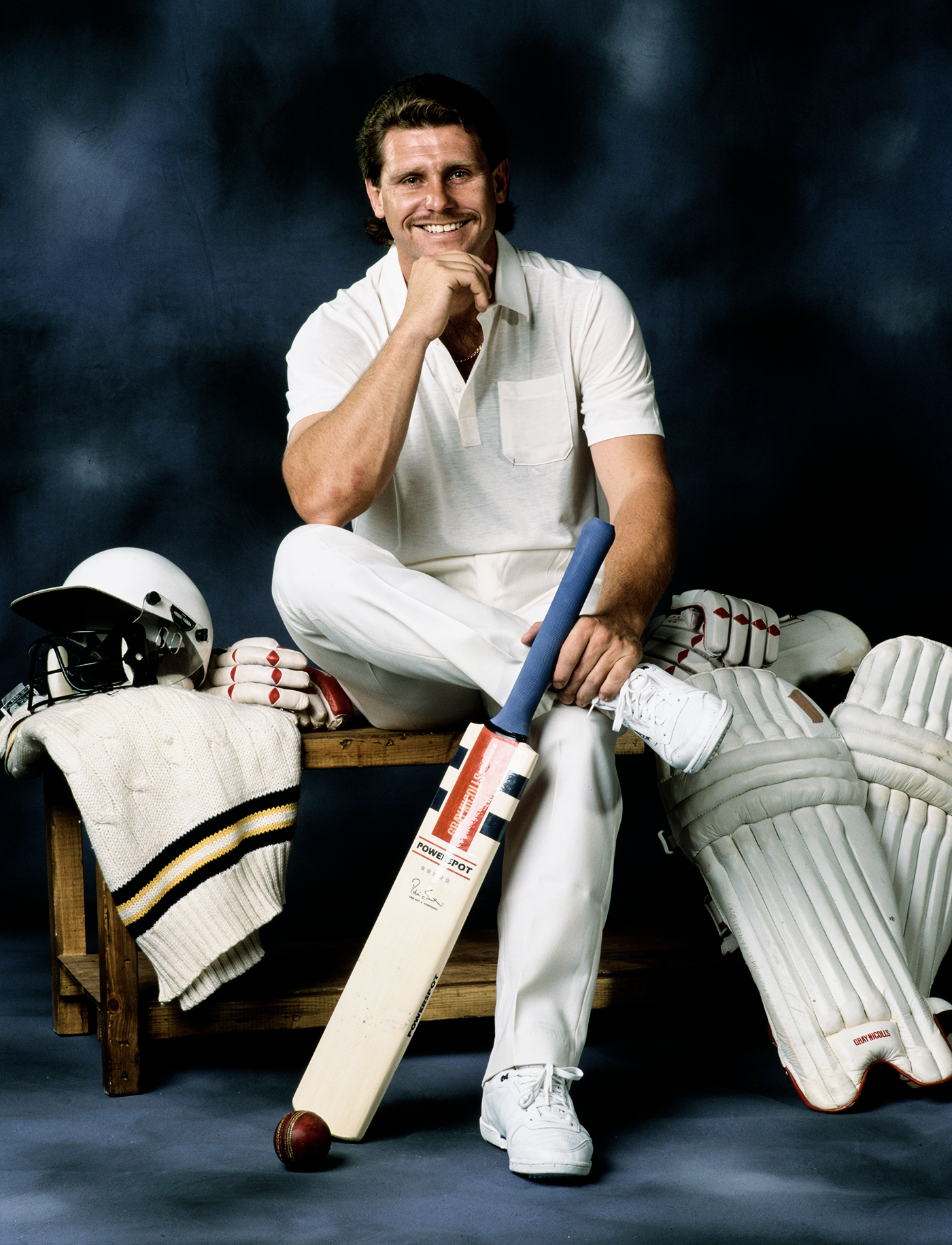

Made in Hants: Smith in a 1985 County Championship match

© Getty Images

Barry talked about the coaching book he wrote some 53 years ago in which Robin was photographed as the model pupil at the age of nine. That's how good he was, even then. He could play all the shots, most of them strongly and always in balance. Barry didn't have to tell him much - though Robin dismissed this as nonsense. Well, he would: modest to a fault. When breakfast finished, we hugged. For the last time.

I first knew him when he came to Hampshire in 1982 on the back of his brother's successful signing two years earlier. Oh my days, could he bat! He was raised by a joyous if quirky father who pushed him hard, and the kindest, most gentle, ballet-teaching mother. They brought in a coach, the former Natal batter, clear-thinking Grayson Heath, and the triangle of learning and improvement was set in stone. Robin played mainly forward and drove straight and off his toes with splendid certainty. Those who tried to force him back were viciously cut and pulled. It was simple, exciting and effective. Obviously to us all at the time, a star was born.

He loved a night out and, on occasion, only just beat the cup of tea his father brought to his youngest son's bedroom at 5am, 20 minutes before they left for rugby training in the winter and for cricket nets in the summer.

In a school rugby match once, Robin, playing at inside centre, received the ball from his fly half on the halfway line and burst past seemingly every member of the opposition before speeding down the right wing towards the try line. Alongside him, at full tilt, was his father, John, dressed as always in white shoes, socks, shorts and safari shirt. Screaming support ("C'mon my boy, faster my boy, c'mon Robin, run Robin, run…") John threw himself over the line on top of his son before celebrating the fantastic try as if he himself had scored in a World Cup final. Both emerged coated in mud, one of them smiling in acute embarrassment.

Back in England, the Hampshire net area wasn't big enough for Robin, and the club coach banned him from hitting sixes, such was the high cost of cricket balls not returned by local residents. In match intensity, batting with him was great fun and the trick was to get him to show off more than his reticence would naturally allow. After the Barry Richards sign-off came the Viv Richards appraisal - "Judgie, man, he got a big heart man, big courage, y'know, and he strikes the ball like no one else man. I love that guy. When he walks in I secretly hope he makes a few, y' know, but only just a few, you understand!" The Judge's R-rated battle with Ian Bishop in Antigua might have helped prompt that little narration.

Glory days: the author and Smith revel in the 1992 Benson and Hedges Cup title win

© PA Photos

His first Test was against Viv's men at Headingley in 1988, after a breathtaking televised cameo in the Benson and Hedges Cup final at Lord's, in which he blistered the pacy Derbyshire attack. Kitten-nervous, he walked in at Headingley to face his pal Macko and clipped the first ball off his legs for a couple. Robin said it was a deliberately gentle leg-stump half-volley. Viv agreed but didn't seem to mind in the slightest. Macko simply denied it, somewhat sheepishly.

The next ball was a bouncer, and after that, he was away; 4236 runs at 43.67 in 62 Test matches at a time when the England team was disjointed. God knows why not more - matches, that is. He was 32 and done up as a Test cricketer. Daft. With a little more self-belief, he'd have played a hundred matches and averaged 48. Honest, he would. He had the game. They say he was crap against spin but he averaged 63 against India and 67 against Sri Lanka. Warnie got him a few times, the first of them just a few balls after the one "of the century" that did for Mike Gatting at Old Trafford in 1993. Have a look at it on YouTube. It's a belter and does not define the Judge as weak against spin in any way or form. But once it's a media story and the Judge hears about it, he shrinks.

After the 1988 Cup final, we won twice again, in 1991 and 1992. Our hero was Player of the Match both times. He played on for Hampshire into his forties and is, in my view, the county's greatest ever cricketer, pipping Marshall to this accolade. This is not to say he's the best cricketer to play for the club, because Richards, Gordon Greenidge, Marshall and Warne battle for that title (Wasim Akram played a few games for the county too) but simply to say that when it mattered, and consistently so over a very long time, he turned on the magic.

Amid these serious judgements, you have to laugh. Robin was naive beyond belief in his vibrant youth. We once drove to Cardiff with a plan. Robin travelled with his brother in their red-and-white Porsche - posers - and behind were Paul Terry and I in something rather less glamorous. A few miles before the Severn Bridge, Chris, or Kippy as we all knew him, asked him to get their passports out.

"Passport?" said the Judge.

"Yes, we're heading into Wales now."

"Er, I haven't got my passport with me, Kips. No one said."

"Jeepers, Judge, we've got a problem."

Cricket wrapped its arms around Robin Smith, and true happiness evaded him after he left the sport behind

© Getty Images

They pulled in to a service station, us tucked in behind them.

"Judge hasn't got his passport."

"Hmm," said I.

"Well, either he gets a cab back to Southampton and then trains it to Cardiff, or…."

"What?"

"We hide you in my boot until we've crossed through immigration."

"Whaaat?!"

And in he climbed and there he stayed until the Hilton somewhere near the city centre

That took some living down.

Now he's passed on, after years of battling the demon drink while caring for his mother and father, and more recently his girlfriend, Karin, who is confined to a wheelchair. He'd done it tough, like really tough. Allan Lamb, with whom he batted in that first Test innings, helped keep him afloat with typical humour and unwavering commitment to a team-mate and friend he valued highly. Rod Bransgrove, the Hampshire chairman, treated Robin as he would his own son. A number of very good people gave him their best shot but true happiness eluded Robin in the years after professional cricket and he never found an alternative.

He would talk of two very different people, Robin Smith and the Judge, and sadly explain how he could no longer be the latter. The Judge was no hellraiser but he was a fabulous bloke and a brilliant cricketer who took on the best and most threatening in the world and often won. Robin Smith was a beautiful man, suddenly exposed to a world that no longer made sense. Cricket had wrapped its arms around him and then pushed him from the door. The streets outside numbed him and the future held next to nothing of the blue-sky idealism under which he had previously flourished.

At a party in Perth we sat close together on a small sofa and he explained how hard he found being at the Optus Stadium during the Test, and how, more generally, he could no longer cope with the adulation. Now he doesn't have to. Instead, we hope he can chill with the other wonderful cricketers who have left us too early, while reflecting on the glory days, the friendships, the fun and the family at home he so adored. We salute Margaux and Harrison - his two kids, grown up and forging their own path - for their love of a man who gave the game he loved every inch of himself.

Here is the message I have sent to the many friends of us both who have been in touch:

"It's awful… but his life had not become easy. A very special person and a thrilling cricketer has gone. I loved him - as did so many all over the world - and was lucky to be with him amongst numerous dear friends last week when his great spirit still shone brightly. May God rest his mighty soul."

Mark Nicholas, the former Hampshire captain, is a TV and radio presenter and commentator

© ESPN Sports Media Ltd.