Patrick Eagar

'You need to be broad-minded as a cricket photographer'

Patrick Eagar, who this summer announced his retirement from actively covering cricket, looks at his life and times in the game

Patrick Eagar, who this summer announced his retirement from actively covering cricket, looks at his life and times in the game

"You could probably turn up in the last 10 minutes of an ODI and get the picture of the day" Nagraj Gollapudi / © ESPNcricinfo Ltd

I have done 325 Tests, all completed ones. That includes 98 Ashes Tests. Richie Benaud and John Woodcock, the former Times cricket correspondent, have probably seen more.

We are in the world of the [photo] agencies. We are in the world of high speed. We are in the world of if something happens in a Test match, it is not the best picture that you are giving out, it is the first picture. It is a shame, because however good you are, you are not always going to edit at high speed.

My first real camera was given to me by my grandmother when I was eight or nine. I still have it.

During the 1983 World Cup I was photographing the tournament for the organisers. They needed head-and-shoulders' photographs of the finalists. I made sure I had got the ones of the teams who were [thought to be] going to win - except, I had not got India and they got to the semi-finals! Again, I thought England were going to win at Old Trafford, as they were the home team. I was not too bothered. The deadline for the programme was the next day, nine in the morning. Halfway through the match I suddenly realised India had a very good chance of winning it and getting to the final. So I knocked at their dressing-room door and said, can I come take photos? It was not entirely convenient, but in those days you knew the players and so they said yes, of course. Imagine that happening now!

You try very hard to forget the mistakes, otherwise they prey on you.

The worst touch-and-go for me was the semi-final of the 1999 World Cup between Australia and South Africa, which came down to the last ball. It had to be done on the remote-control camera with a quite wide view, because where I was [in the ground] was no good. The camera I had been using had been shooting blank frames occasionally. In those days there were only 36 pictures on your remote camera. My first shot that day was fine and better than my rivals', but the rest of the sequence was all blank. Phew!

I wish I had bought better lenses earlier on.

I had been doing photography for seven to eight years when the Test and County Cricket Board let [us] into Test matches for the first time, in 1972. The next summer, West Indies were coming to England. I reckoned I'd love to see what cricket in the West Indies was like and so I thought to photograph the [1972-73] West Indies-Australia Test series. But in those days travelling was really expensive. It was unknown territory. My father arranged for me to stay with somebody in Barbados. It was a big gamble. I did mostly background stuff: cricket in the cane fields, cricket on the beach, and the Observer magazine used it, and that paid for most of my trip.

The most important thing you have got is your time, and if you compromise on quality you are not going to get the best out of it.

In 1974 I travelled to Australia and the time difference worked for me. By then I had been working for the Sunday Times fairly regularly and I told them I would send pictures. They thought it would not work. In Perth I took pictures of Doug Walters making a hundred in a session. When I saw the paper, it was a tiny, tiny picture. They said, "We did not think it was going to arrive, so we did not leave any room." In the next Test they carried an eight-column picture.

Edgbaston 1999: done by remote control © Patrick Eagar

I have got no news sense at all. I am helpless if you wave news in front of me.

I got the idea of having a remote-control camera shoot wide pictures from reading about it in Sports Illustrated. At a county match in Kent I put the camera on top of the television tower and then unwound a 450-foot cable across the ground to where I was sitting. People tripped over it but it worked beautifully. Then a television technician, who did not know that I'd got permission, decided the camera was a waste of space and moved it. I ended up photographing the sky.

It helps if the player knows you.

During the last Ashes I tried over and over again to shoot and put the crowds and the colour in context. I had looked at the stuff I had done four years ago and it was all close-up stuff, so I decided to change it this time. Of course, being a freelancer, I can afford to do it.

If you read Woodcock's copy and if I had a picture of everything he mentioned, I had done well.

Viv Richards was always a bit scary. I found Garry Sobers absolutely astonishing in every respect. Shane Warne… I am trying to think of people who would be regarded as the greatest in 100 years' time. Sachin Tendulkar, a difficult subject to photograph, is there.

Some photographers sit in the same place every day. You think, "Hang on, you're just after one part of it. You're not interested in the whole of it." You need to be broad-minded.

After the famous win at Headingley in 1981, three of us photographers barged into the England dressing room. Botham was sitting there with a pack of cigars in his hands. Then he put one into his mouth, and I told myself, "Bad image." I was quite happy with the ones I got, but in that picture he was pensive.

I took a picture of Steve Waugh playing the forward-defensive from the square position in the 1989 Ashes in England. Many people liked it, including Steve. It was a very obvious one to do. It was a patient innings and he was very happy to play an exaggerated forward-defensive stroke against our spinners, and I just liked to click him.

You need to see the face of the batsman.

Tendulkar times the ball so well, you don't often get the impression that he is hitting the ball. He'd score half a dozen fours and you might not remember any of them. You just remember the ability to manoeuvre the ball in such a way that it goes to the boundary. You have to be square probably [to shoot him]. No other position would work for him.

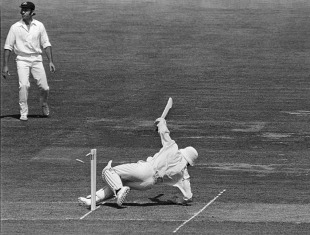

Roy Fredericks treads on his stumps after hooking Dennis Lillee for six in the 1975 World Cup © Patrick Eagar

The nearest that someone came to breaking my camera was Botham at Trent Bridge [1983]. He was very angry with the press. They had written something he did not like. He made a hundred against New Zealand and he spent most of the morning trying to hit the ball into the press box. I was underneath. One shot took the top off the wood of the advertising boards, which flew into the six inches of space between myself and another photographer.

The trouble with crowd photography is, you have to fit it in between the action. If you do not watch the ball [you could miss] the picture of the day, picture of the match, could even be the picture of the year. You turn away from the cricket at your peril.

When Monty Panesar first got picked for England, they asked him about his formative years. He said he was given a book and in that there was this sequence of photographs of Bishan Singh Bedi bowling and he had studied every photograph and he had learned bowling from them. They were my sequence. The fact that my pictures had got into a book and a young player had looked at them and said, "I'm going to do that" is one of my proudest moments.

In my cynical moments, I have suggested that you could probably turn up in the last 10 minutes of an ODI and get the picture of the day. I have never done it. You could, though.

The best spin bowler I have ever, ever seen is Shane Warne. I would watch the ball like a movie. When he started in 1993, the ball would move through the air starting from middle stump, and by the time it pitched it was three foot outside leg stump, and by the time it spun back, as Mike Gatting discovered, it would take the top of off stump. You can't photograph that as a still. You can photograph the result of it.

With a fast bowler it is easy to get as they get into extreme positions.

You have not got time to get involved as a photographer. If you do, you could ignore things. But there have been occasions - the 2005 Ashes, I lost it once, maybe twice. At Edgbaston towards the end I did well to hang on to my emotions. But at Trent Bridge I remember the suspense vividly: Shane Warne started taking wickets towards the end. I started getting hysterical. Couldn't bear it. I yelled. No one cared.

Imran Khan once said: "I would only have my photograph taken by Patrick."

In the old days, when I started, they used plate cameras. I did not do it myself but if you took one picture on a plate camera it would be at least 20 seconds before you could take another one. You had to cover the film up, take the whole plate out, put another plate in, re-cock the shutter, take the sheet thing out of the plate, and then you were ready to go. By then you might have to re-focus and the sun might have gone in, and various such issues. Now you just set your camera, you have a fully charged battery which will last you the whole day, a memory card that can hold 1000 photos, and you just press the button.

If you take so many pictures, actually finding a good one is quite difficult.

As a photographer my best Test would be the centenary match in 1977 in Melbourne because it swung so dramatically every day. The rhythm of it was so perfect.

Nagraj Gollapudi is an assistant editor at ESPNcricinfo

© ESPN Sports Media Ltd.